Review of Following the Money Wealthy Women Feminism and the American Suffrage Movement

A move to fight for women's correct to vote in the United Kingdom finally succeeded through laws in 1918 and 1928. It became a national movement in the Victorian era. Women were not explicitly banned from voting in United kingdom until the Reform Act 1832 and the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. In 1872 the fight for women's suffrage became a national movement with the germination of the National Lodge for Women's Suffrage and later on the more influential National Union of Women'southward Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Also equally in England, women'due south suffrage movements in Wales, Scotland and other parts of the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland gained momentum. The movements shifted sentiments in favour of woman suffrage by 1906. It was at this betoken that the militant campaign began with the formation of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[1]

The outbreak of the Commencement World War on 4 August 1914 led to a suspension of party politics, including the militant suffragette campaigns. Lobbying did accept place quietly. In 1918 a coalition government passed the Representation of the People Deed 1918, enfranchising all men over 21, as well as all women over the age of xxx who met minimum property qualifications. This human activity was the start to include almost all adult men in the political arrangement and began the inclusion of women, extending the franchise by 5.6 meg men[2] and 8.4 million women.[iii] In 1928 the Bourgeois regime passed the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act equalizing the franchise to all persons over the historic period of 21 on equal terms.

Background [edit]

Until the 1832 Great Reform Act specified 'male person persons', a few women had been able to vote in parliamentary elections through property ownership, although this was rare.[iv] In local authorities elections, women lost the right to vote under the Municipal Corporations Deed 1835. Single women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This correct was confirmed in the Local Government Human activity 1894 and extended to include some married women.[5] [6] [7] By 1900, more than 1 million women were registered to vote in local government elections in England.[8] Women were also included in the suffrage on the same terms as men (i.e., all parishioners over 21) in the unique set of border polls carried out from 1915 to 1916 under the Welsh Church Act 1914.[ix] These were held to determine whether the residents of parishes which straddled the political edge between England and Wales wished their ecclesiastical parishes and churches to remain with the Church of England or to join the disestablished Church in Wales when it was gear up. The Welsh Church building Human action 1914 had required the Welsh Church Commissioners to ascertain the views of the "parishioners", and they decided "to allow a voice to all persons, male or female, of 21 years of age or over".[9] The polls are therefore one of the earliest examples, if not the earliest, of an official poll being carried out in the Uk nether a system of universal adult suffrage, though also permitting non-resident ratepayers of either gender to vote.[10]

Both before and afterwards the 1832 Reform Act at that place were some who advocated that women should have the right to vote in parliamentary elections. After the enactment of the Reform Act, the MP Henry Chase argued that any adult female who was single, a taxpayer and had sufficient property should be allowed to vote. One such wealthy woman, Mary Smith, was used in this speech equally an example.

The Chartist Move, which began in the belatedly 1830s, has too been suggested to have included supporters of female suffrage. There is some evidence to suggest William Lovett, i of the authors of the People's Charter wished to include female suffrage equally one of the campaign's demands but chose not to on the grounds that this would delay the implementation of the lease. Although there were female Chartists, they largely worked toward universal male suffrage. At this time most women did not have aspirations to gain the vote.

There is a poll book from 1843 that clearly shows xxx women's names amidst those who voted. These women were playing an active role in the election. On the curlicue, the wealthiest female person elector was Grace Chocolate-brown, a butcher. Due to the high rates that she paid, Grace Brown was entitled to four votes.[11]

Lilly Maxwell cast a loftier-profile vote in Uk in 1867 after the Great Reform Human action of 1832.[12] Maxwell, a shop possessor, met the holding qualifications that otherwise would have fabricated her eligible to vote had she been male person. In error, her name had been added to the election register and on that basis she succeeded in voting in a by-ballot – her vote was later declared illegal by the Courtroom of Common Pleas. The case gave women'due south suffrage campaigners great publicity.

Outside force per unit area for women'southward suffrage was at this time diluted past feminist issues in general. Women'southward rights were becoming increasingly prominent in the 1850s as some women in higher social spheres refused to obey the gender roles dictated to them. Feminist goals at this time included the right to sue an ex-husband afterward divorce (achieved in 1857) and the correct for married women to own property (fully accomplished in 1882 after some concession by the regime in 1870).

The issue of parliamentary reform declined along with the Chartists later on 1848 and only reemerged with the ballot of John Stuart Manufactory in 1865. He stood for office showing direct support for female suffrage and was an MP in the run up to the second Reform Act.

Early suffragist societies [edit]

In the same year that John Stuart Manufacturing plant was elected (1865), the first ladies' discussion society, Kensington Guild, was formed, debating whether women should exist involved in public affairs.[xiii] Although a society for suffrage was proposed, this was turned down on the grounds that it might be taken over by extremists.

Later on that year Leigh Smith Bodichon formed the commencement Women's Suffrage Committee and inside a fortnight nerveless nearly one,500 signatures in favour of female suffrage in advance to the second Reform Neb.[14]

The Manchester Guild for Women's Suffrage was founded in Feb 1867. Its secretary, Lydia Becker, wrote messages both to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and to The Spectator. She was likewise involved with the London group, and organised the collection of more signatures. Lydia Becker reluctantly agreed to exclude married women from the "Married Women's Property Act" reform need.[15]

In June the London grouping split, partly a result of party allegiance, and partly the result of tactical issues. Conservative members wished to move slowly to avert alarming public stance, while Liberals generally opposed this credible dilution of political conviction. As a issue, Helen Taylor founded the London National Society for Women'due south Suffrage, which set upward stiff links with Manchester and Edinburgh. In Scotland one of the earliest societies was the Edinburgh National Society for Women'due south Suffrage.[xvi]

Although these early splits left the movement divided and sometimes leaderless, it allowed Lydia Becker to have a stronger influence. The suffragists were known as the parliamentarians.

In Ireland, Isabella Tod, an anti-Home Rule Liberal and campaigner for girls didactics, established the Northward of Ireland Women's Suffrage Social club in 1873 (from 1909, still based in Belfast, the Irish WSS) Determined lobbying past the WSS ensured the 1887 Human activity creating a new municipal franchise for Belfast (a city in which women predominated due to heavy employment in mills) conferred the vote on "persons" rather than men. This was xi years before women elsewhere Ireland gained the vote in local government elections.[17] The Dublin Women's Suffrage Association was established in 1874. As well as campaigning for women's suffrage, information technology sought to advance women'southward position in local government. In 1898, it changed its name to the Irish Women's Suffrage and Local Government Association.

Formation of a national motility [edit]

Women's political groups [edit]

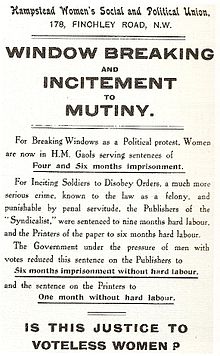

A handbill complaining about sexual discrimination during the move.

Although women'south political party groups were not formed with the aim to achieve women'south suffrage, they did have two key effects. Firstly, they showed women who were members to be competent in the political arena and equally this became clear, secondly, information technology brought the concept of female person suffrage closer to credence.

The Primrose League [edit]

The Primrose League (1883 - 2004) was gear up to promote Conservative values through social events and supporting the community. As women were able to join, this gave females of all classes the ability to mix with local and national political figures. Many also had important roles such as bringing voters to the polls. This removed segregation and promoted political literacy among women. The League did non promote women'south suffrage equally ane of its objectives.[ commendation needed ]

The Women's Liberal Associations [edit]

Although there is testify to advise that they were originally formed to promote female franchise (the kickoff existence in Bristol in 1881), WLAs ofttimes did not concord such an calendar. They operated independently from the male groups, and did become more active when they came under the control of the Women's Liberal Federation, and canvassed all classes for support of women's suffrage and against domination.

There was pregnant support for woman suffrage in the Liberal Party, which was in power after 1905, only a handful of leaders, especially H. H. Asquith, blocked all efforts in Parliament.[18]

Pressure groups [edit]

The campaign start adult into a national motion in the 1870s. At this point, all campaigners were suffragists, not suffragettes. Up until 1903, all campaigning took the constitutional approach. It was later on the defeat of the first Women's Suffrage Neb that the Manchester and London committees joined together to gain wider support. The chief methods of doing and so at this fourth dimension involved lobbying MPs to put frontward Private Member'due south Bills. However such bills rarely pass and and then this was an ineffective way of actually achieving the vote.

In 1868, local groups amalgamated to form a series of close-knit groups with the founding of the National Order for Women'southward Suffrage (NSWS). This is notable as the outset attempt to create a unified front to suggest women'south suffrage, but had little result due to several splits, one time once again weakening the entrada.

Upward until 1897, the campaign stayed at this relatively ineffective level. Campaigners came predominantly from the landed classes and joined together on a small scale only. In 1897 the National Union of Women'south Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was founded past Millicent Fawcett. This society linked smaller groups together and also put pressure level on non-supportive MPs using various peaceful methods.

Pankhursts and suffragettes [edit]

Founded in 1903, the Women'due south Social and Political Union (WSPU) was tightly controlled by the three Pankhursts, Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), and her daughters Christabel Pankhurst (1880–1958) and Sylvia Pankhurst (1882–1960).[19] It specialized in highly visible publicity campaigns such as big parades. This had the event of energizing all dimensions of the suffrage movement. While in that location was a bulk of support for suffrage in parliament, the ruling Liberal Party refused to allow a vote on the issue; the upshot of which was an escalation in the suffragette campaign. The WSPU, in dissimilarity to its allies, embarked on a campaign of violence to publicize the issue, even to the detriment of its ain aims.[twenty]

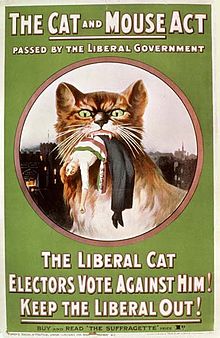

The True cat and Mouse Human activity was passed past Parliament in an try to prevent suffragettes from condign martyrs in prison. It provided for the release of those whose hunger strikes and forced feeding had brought them sickness, as well as their re-imprisonment once they had recovered. The result was even greater publicity for the cause.[21]

The tactics of the WSPU included shouting down speakers, hunger strikes, stone-throwing, window-slap-up, and arson of unoccupied churches and country houses. In Belfast, when in 1914 the Ulster Unionist Quango appeared to renege on an earlier commitment to women's suffrage,[22] the WSPU's Dorothy Evans (a friend of the Pankhursts) alleged an terminate to "the truce nosotros have held in Ulster." In the months that followed WSPU militants (including Elizabeth Bell, the offset adult female in Ireland to qualify as a medico and gynaecologist) were implicated in a series of arson attacks on Unionist-owned buildings and on male recreational and sports facilities.[23] In July 1914, in a program hatched with Evans, Lillian Metge, who was previously function of a 200-strong deputation that charged George Five equally he entered Buckingham Palace, bombed Lisburn Cathedral.[24]

Historian Martin Pugh says, "militancy clearly damaged the cause."[25] Whitfield says, "the overall effect of the suffragette militancy, was to set back the crusade of women'due south suffrage."[26] Historian Harold Smith, citing historian Sandra Holton, has argued that by 1913 WSPU gave priority to militancy rather than obtaining the vote. Their boxing with Liberals had become a "kind of holy war, so important that it could not be called off even if continuing it prevented suffrage reform. This preoccupation with the struggle distinguished the WSPU from that by the NUWSS, which remained focused on obtaining women's suffrage."[27]

Smith concludes:[28]

Although non-historians often causeless the WSPU was primarily responsible for obtaining women's suffrage, historians are much more than skeptical about its contribution. It is generally agreed that the WSPU revitalized the suffrage entrada initially, simply that its escalation of militancy later 1912 impeded reform. Recent studies have shifted from claiming that the WSPU was responsible for women's suffrage to portraying it as an early form of radical feminism that sought to liberate women from a male-centered gender system.

Beginning World War [edit]

The greater suffrage efforts halted with the outbreak of Earth War I. While some activity continued, with the NUWSS standing to lobby peacefully, Emmeline Pankhurst, convinced that Germany posed a danger to all humanity, persuaded the WSPU to halt all militant suffrage activity.

Parliament expands suffrage 1918 [edit]

During the war, a select group of parliamentary leaders decided on a policy that would expand the suffrage to all men over the age of 21, and propertied women over the historic period of 30. Asquith, an opponent, was replaced as prime minister in late 1916 by David Lloyd George who had, for his first x years as an MP, argued confronting women having the franchise.

During the state of war there was a serious shortage of athletic men and women were able to take on many of the traditionally male roles. With the approval of the trade unions, "dilution" was agreed upon. Complicated factory jobs handled past skilled men were diluted or simplified so that they could exist handled by less skilled men and women. The result was a big increase in women workers, concentrated in munitions industries of highest priority to winning the war. This led to a increased societal understanding of what work women were capable of. Some believe that the franchise was partially granted in 1918 because of a pass up in anti-suffrage hostility caused by pre-war militant tactics. However, others believe that politicians had to cede at to the lowest degree some women the vote and then every bit to avoid the promised re-resurgence of militant suffrage activity. Many of the major women'south groups strongly supported the war try. The Women's Suffrage Federation, based in the east end and led by Sylvia Pankhurst, did not. The federation held a pacifist stance and created co-operative factories and nutrient banks in the East End to support working class women throughout the war. Until this betoken suffrage was based on occupational qualifications of men. Millions of women were at present coming together those occupational qualifications, which in any case were and so old-fashioned that the consensus was to remove them. For example, a male voter who joined the Army might lose the right to vote. In early 1916, suffragist organizations privately agreed to downplay their differences, and resolve that whatsoever legislation increasing the number of votes should also enfranchise women. Local government officials proposed a simplification of the old system of franchise and registration, and the Labour cabinet fellow member in the new coalition regime, Arthur Henderson, called for universal suffrage, with an age cutoff of 21 for men and 25 for women. Nigh male political leaders showed anxiety near having a female person bulk in the new electorate. Parliament turned over the issue to a new Speakers Briefing, a special commission from all parties from both houses, chaired by the Speaker. They began meeting in October 1916, in hugger-mugger. A bulk of 15 to 6 supported votes for some women; by 12 to 10, it agreed on a higher age cut off for women.[29] Women leaders accepted a cutoff age of xxx in society to get the vote for almost women.[30]

Finally in 1918, Parliament passed an act granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5, and graduates of British universities. Near 8.four 1000000 women gained the vote.[31] In November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Deed 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected into the House of Commons.[31] By 1928 the consensus was that votes for women had been successful. With the Bourgeois Political party in full command in 1928, information technology passed the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act that extended the voting franchise to all women over the age of 21, granting women the vote on the same terms as men,[32] [33] although 1 Conservative opponent of the beak warned that it risked splitting the party for years to come up.[34]

Women in prominent roles [edit]

Emmeline Pankhurst was a fundamental figure gaining intense media coverage of the women'southward suffrage movement. Pankhurst, alongside her two daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, founded and led the Women's Social and Political Union, an arrangement that was focused on direct action to win the vote. Her husband, Richard Pankhurst, as well supported women suffrage ideas since he was the author of the first British adult female suffrage bill and the Married Women's Property Acts in 1870 and 1882. Afterwards her husband's death, Emmeline decided to motion to the forefront of the suffrage battle. Forth with her two daughters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst, she joined the National Union of Women'southward Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). With her feel with this system, Emmeline founded the Women'southward Franchise League in 1889 and the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903.[35] Frustrated with years of authorities inactivity and false promises, the WSPU adopted a militant stance, which was and then influential it was afterwards imported into suffrage struggles worldwide, nigh notably by Alice Paul in the United States. After many years of struggle and adversity, women finally gained suffrage but Emmeline died shortly afterwards this.[36]

Some other fundamental figure was Millicent Fawcett. She had a peaceful approach to issues presented to the organisations and the mode to become points across to society. She supported the Married Women's Belongings Deed and the social purity campaign. Ii events influenced her to become even more involved: her husband's death and the division of the suffrage movement over the issue of affiliation with political parties. Millicent, who supported staying independent of political parties, fabricated sure that the parts separated came together to go stronger by working together. Considering of her actions, she was fabricated president of the NUWSS.[37] In 1910–1912, she supported a pecker to requite vote rights to unmarried and widowed females of a household. By supporting the British in Earth State of war I, she idea women would be recognised as a prominent part of Europe and deserved basic rights such as voting.[38] Millicent Fawcett came from a radical family unit. Her sister was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson an English dr. and feminist, and the first woman to gain a medical qualification in United kingdom. Elizabeth was elected mayor of Aldeburgh in 1908 and gave speeches for suffrage.[39]

Emily Davies became an editor of a feminist publication, Englishwoman'south Periodical. She expressed her feminist ideas on newspaper and was also a major supporter and influential figure during the twentieth century. In addition to suffrage, she supported more rights for women such as admission to education. She wrote works and had power with words. She wrote texts such as Thoughts on Some Questions Relating to Women in 1910 and College Education for Women in 1866. She was a big supporter in the times where organisations were trying to reach people for a modify.[40] With her was a friend named Barbara Bodichon who also published articles and books such as Women and Piece of work (1857), Enfranchisement of Women (1866), and Objections to the Enfranchisement of Women (1866), and American Diary in 1872.[41]

Mary Gawthorpe was an early on suffragette who left educational activity to fight for women's voting rights. She was imprisoned after heckling Winston Churchill. She left England after her release, eventually emigrating to the United States and settling in New York. She worked in the trade spousal relationship movement and in 1920 became a full-time official of the Amalgamated Article of clothing Workers Marriage. In 2003, Mary's nieces donated her papers to New York University.[42]

Male suffragists [edit]

Males were too present in the suffrage movement.

Laurence Housman [edit]

Laurence Housman was a male feminist who devoted himself to the suffrage move. Most of his contributions were through creating art, such as propaganda, with the intent of helping women in the movement to better express themselves,[43] influencing people to join the movement[44] and informing people almost particular suffrage events such as the 1911 Census protestation.[45] He and his sister, Clemence Housman, created a studio called the Suffrage Atelier which aimed to create propaganda for the suffrage movement.[46] This was significant because he produced a infinite for women to create propaganda to better assist the suffrage movement and, at the same time, earn money by selling the art.[43] Also, he created propaganda such equally the Anti-Suffrage Alphabet,[47] and wrote for many women's newspapers.[47] Additionally, he too influenced other men to aid the motility.[44] For case, he formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage with State of israel Zangwill, Henry Nevinson and Henry Brailsford, hoping to inspire other men to participate in the movement.[44]

Legacy [edit]

Whitfield concludes that the militant campaign had some positive furnishings in terms of attracting enormous publicity, and forcing the moderates to ameliorate organise themselves, while also stimulating the organization of the antis. He concludes:[48]

The overall effect of the suffragette militancy, however, was to set dorsum the cause of women'southward suffrage. For women to gain the right to vote it was necessary to demonstrate that they had public opinion on their side, to build and consolidate a parliamentary bulk in favour of women'due south suffrage and to persuade or pressure the government to introduce its own franchise reform. None of these objectives was achieved.

The Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst Memorial in London was first defended to Emmeline Pankhurst in 1930, with a plaque added for Christabel Pankhurst in 1958.

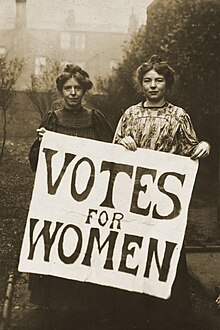

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Women being given the right to vote, a statue of Millicent Fawcett was erected in Parliament Square, London in 2018.[49] The photo colouriser Tom Marshall released a series of photos to marking the 100th anniversary of the vote, including an image of suffragettes Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst, which appeared on The Daily Telegraph front page on 6 Feb 2018.[l]

Timeline [edit]

A suffragette arrested in the street by two police officers in London in 1914

- 1818: Jeremy Bentham advocates female suffrage in his book A Program for Parliamentary Reform. The Vestries Human activity 1818 allowed some unmarried women to vote in parish vestry elections[8]

- 1832: Great Reform Human activity – confirmed the exclusion of women from the electorate.

- 1851: The Sheffield Female Political Clan is founded and submits a petition calling for women'due south suffrage to the Firm of Lords.

- 1864: The first Contagious Disease Act is passed in England, which is intended to control venereal disease by having prostitutes and women believed to be prostitutes locked away in hospitals for examination and handling. When information broke to the general public most the shocking stories of brutality and vice in these hospitals, Josephine Butler launched a campaign to go it repealed. Many have since argued that Butler's campaign destroyed the conspiracy of silence around sexuality and forced women to act in protection of others of their sex. In doing so, clear linkages sally between the suffrage movement and Butler's campaign.[51]

- 1865: John Stuart Factory elected as an MP showing direct back up for women'southward suffrage.

- 1867: Second Reform Act – Male franchise extended to ii.5 million

- 1869: Municipal Franchise Deed gives single women ratepayers the right to vote in local elections.[five] [vi] [7]

- 1883: Conservative Primrose League formed.

- 1884: Third Reform Human activity – Male electorate doubled to 5 1000000

- 1889: Women's Franchise League established.

- 1894: Local Government Deed (women could vote in local elections, become Commune Councillors [though non their Chairmen], Poor Law Guardians, act on School Boards)

- 1894: The publication of C.C. Stopes'southward British Freewomen, staple reading for the suffrage movement for decades.[52]

- 1897: National Matrimony of Women's Suffrage Societies NUWSS formed (led by Millicent Fawcett).

- 1903: Women'due south Social and Political Union WSPU is formed (led by Emmeline Pankhurst)

- 1904: Militancy begins. Emmeline Pankhurst interrupts a Liberal Party meeting.[53]

- February 1907: NUWSS "Mud March" – largest open air demonstration ever held (at that point) – over 3000 women took part. In this twelvemonth, women were admitted to the register to vote in and represent election to principal local authorities.

- 1907: The Artists' Suffrage League founded

- 1907: The Women's Freedom League founded

- 1908: Actresses Franchise League founded

- 1908: Women Writers' Suffrage League founded

- 1908: in November of this twelvemonth, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, a fellow member of the pocket-size municipal borough of Aldeburgh, Suffolk, was selected as mayor of that boondocks, the offset woman to so serve.

- 1907, 1912, 1914: major splits in the WSPU

- 1905, 1908, 1913: 3 phases of WSPU militancy (Ceremonious Disobedience; Destruction of Public Holding; Arson/Bombings)

- v July 1909: Marion Wallace Dunlop went on the showtime hunger strike – was released afterwards 91 hours of fasting

- 1909 The Women's Tax Resistance League founded

- September 1909: Force feeding introduced to hunger strikers in English prisons

- 1910: Lady Constance Lytton disguised herself as a working-class seamstress, Jane Wharton, and was arrested and endured strength feeding that cut down her life span considerably[54]

- Feb 1910: Cross-Political party Conciliation Committee (54 MPs). Conciliation Bill (that would enfranchise women) passed its 2nd reading by a bulk of 109 merely H. H. Asquith refused to give it more parliamentary time

- November 1910: Asquith changed the Bill to enfranchise more than men instead of women

- 18 November 1910: Black Friday[55]

- October 1912: George Lansbury, Labour MP, resigned his seat in support of women's suffrage

- Feb 1913: David Lloyd George's house blown up past WSPU[56] despite his support for women's suffrage.

- April 1913: Cat and Mouse Act passed, assuasive hunger-striking prisoners to be released when their health was threatened and and so re-arrested when they had recovered. The first suffragist to exist released under this act was Hugh Franklin and the 2d was his soon-to-be wife Elsie Duval

- 4 June 1913: Emily Davison walked in front of, and was subsequently trampled and killed by, the Male monarch'due south Horse at The Derby.

- 13 March 1914: Mary Richardson slashed the Rokeby Venus painted by Diego Velázquez in the National Gallery with an axe, protesting that she was maiming a cute woman simply as the government was maiming Emmeline Pankhurst with force feeding

- 4 August 1914: Globe State of war declared in Britain. WSPU activity immediately ceased. NUWSS activity continued peacefully – the Birmingham co-operative of the organisation connected to lobby Parliament and write messages to MPs.

- 1915–16: Border polls under Welsh Church building Human activity 1914 held under universal developed suffrage.

- half dozen February 1918: The Representation of the People Human activity of 1918 enfranchised women over the age of 30 who were either a member or married to a member of the Local Regime Register. About eight.4 million women gained the vote.[31] [57]

- 21 November 1918: the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Human action 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected to Parliament.[31]

- 1928: Women in England, Wales and Scotland received the vote on the same terms as men (over the age of 21) as a result of the Representation of the People Act 1928.[58]

- 1968: The Electoral Police Act (Northern Ireland) removes the belongings franchise requirements making all men and women over 18 in the United Kingdom eligible to vote on equal terms, regardless of gender or grade.

- 1973: The fully enfranchised Northern Irish local elections of May 1973 see the get-go time all government elected officials across the Uk were elected nether universal suffrage.

See also [edit]

- Feminism in the United kingdom

- Lobbying in the Uk

- The Women'southward Library (London)

- Listing of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Timeline of women'southward suffrage

- Women'southward suffrage activism in Leigh

- Women's suffrage in Scotland

- Suffragette bombing and arson campaign

- List of suffragette bombings

- Women in the House of Commons of the United kingdom

- Anti-suffragism

- Suffrage jewellery

- Women's suffrage in the Cayman Islands

- Women's suffrage in Bharat

References [edit]

- ^ See NUWSS.

- ^ Harold 50. Smith (12 May 2014). The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866–1928: Revised 2nd Edition. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN978-1-317-86225-three.

- ^ Martin Roberts (2001). Great britain, 1846–1964: The Claiming of Change. Oxford Academy Press. p. 1. ISBN978-0-19-913373-4.

- ^ Derek Heater (2006). Citizenship in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: A History. Edinburgh University Printing. p. 107. ISBN9780748626724.

- ^ a b Heater (2006). Citizenship in Britain: A History. p. 136. ISBN9780748626724.

- ^ a b "Women'due south rights". The National Athenaeum. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Which Human activity Gave Women the Right to Vote in Britain?". Synonym . Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Female Suffrage before 1918", The History of the Parliamentary Franchise, House of Commons Library, 1 March 2013, pp. 37–9, retrieved xvi March 2016

- ^ a b The Beginning Written report of the Commissioners for Church Temporalities in Wales (1914–xvi) Cd 8166, p 5; 2nd Report of the Commissioners for Church Temporalities in Wales (1917–eighteen) Cd 8472 eight 93, p iv.

- ^ Roberts, Nicholas (2011). "The historical background to the Marriage (Wales) Act 2010". Ecclesiastical Law Journal. 13 (1): 39–56, fn 98. doi:ten.1017/S0956618X10000785. S2CID 144909754. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Sarah Richardson (18 March 2013). "Women voted 75 years before they were legally allowed to in 1918". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Martin Pugh (2000). The March of the Women: A Revisionist Assay of the Campaign for Women's Suffrage, 1866–1914. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–. ISBN978-0-xix-820775-7.

- ^ Dingsdale, Ann (2007). "Kensington Guild (act. 1865–1868) | Oxford Lexicon of National Biography". Oxford Lexicon of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:x.1093/ref:odnb/92488. (Subscription or Britain public library membership required.)

- ^ Hirsch, Pam (7 December 2010). Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon: Feminist, Artist and Rebel. Random House. ISBN9781446413500.

- ^ Holton, Sandra Stanley (1994). ""To Educate Women into Rebellion": Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Cosmos of a Transatlantic Network of Radical Suffragists". The American Historical Review. 99 (4): 1112–1136. doi:10.2307/2168771. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2168771.

- ^ "Edinburgh National Social club for Women's Suffrage". 1876.

- ^ Connolly, S.J.; McIntosh, Gillian (i January 2012). "Chapter 7: Whose City? Belonging and Exclusion in the Nineteenth-Century Urban World". In Connolly, Due south.J. (ed.). Belfast 400: People, Place and History. Liverpool University Press. p. 256. ISBN978-1-84631-635-seven.

- ^ Martin Roberts (2001). Britain, 1846–1964: The Challenge of Change. Oxford UP. p. 8. ISBN9780199133734.

- ^ Jane Marcus, Suffrage and the Pankhursts (2013).

- ^ "The Struggle for Suffrage". historicengland.org.uk. Celebrated England. Retrieved three October 2017.

- ^ Lisa Tickner (1988). The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14. p. 27. ISBN9780226802459.

- ^ History Ireland (24 Jan 2013). "Irish Suffragettes at the fourth dimension of the Home Rule Crunch". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 273–274, 276–278. ISBN9781909556065.

- ^ Toal, Ciaran (2014). "The brutes - Mrs Metge and the Lisburn Cathedral, flop 1914". History Ireland . Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Pugh 2012, p. 152.

- ^ Bob Whitfield (2001). The Extension of the Franchise, 1832–1931. Heinemann. pp. 152–sixty. ISBN9780435327170.

- ^ Harold L. Smith (2014). The British Women'south Suffrage Entrada 1866–1928 second edition. Routledge. p. sixty. ISBN9781317862253.

- ^ Smith (2014). The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866–1928. p. 34. ISBN9781317862253.

- ^ Arthur Marwick, A History of the Modern British Isles, 1914–1999: Circumstances, Events and Outcomes (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), pp. 43–45.

- ^ Millicent Garrett Fawcett (2011). The Women's Victory – and After: Personal Reminiscences, 1911–1918. Cambridge Upward. pp. 140–43. ISBN9781108026604.

- ^ a b c d Fawcett, Millicent Garrett. The Women'due south Victory – and After, Cambridge University Printing, p. 170.

- ^ Malcolm Chandler (2001). Votes for Women C.1900–28. Heinemann. p. 27. ISBN9780435327316.

- ^ D. E. Butler, The Electoral System in Britain 1918–1951 (1954), pp. 15–38.

- ^ Oman, Sir Charles (29 March 1928). "REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE (EQUAL FRANCHISE) BILL. 2nd reading debate". Hansard.

- ^ Atkinson, Diane (1992). The Purple, White and Green: Suffragettes in London, 1906-fourteen. London, England, UK: Museum of London. p. vii. ISBN0904818535. OCLC 28710360.

- ^ Marina Warner, "The Anarchist: Emmeline Pankhurst", Fourth dimension 100,Time Magazine.

- ^ "The Early on Suffrage Societies in the 19th century – a timeline". UK Parliament . Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Jone Johnson Lewis, "Millicent Garrett Fawcett", ThoughtCo.com.

- ^ Jone Johnson Lewis, "Elizabeth Garrett Anderson", ThoughtCo.com.

- ^ Jone Johnson Lewis, "Emily Davies", ThoughtCo.com.

- ^ Jone Johnson Lewis, "Barbara Bodichon", ThoughtCo.com.

- ^ "Guide to the Mary E. Gawthorpe Papers TAM.275". dlib.nyu.edu . Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b Morton, Tara (1 September 2012). "Changing Spaces: fine art, politics, and identity in the home studios of the Suffrage Atelier". Women'south History Review. 21 (4): 623–637. doi:x.1080/09612025.2012.658177. ISSN 0961-2025. S2CID 144118253.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, David (2019). Insubordinate Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London's Radical History (2 ed.). Pluto Press. ISBN978-0-7453-3855-2. JSTOR j.ctvfp63cf.

- ^ Liddington, Jill; Crawford, Elizabeth; Maund, E. A. (2011). "'Women practice not count, neither shall they be counted': Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the 1911 Demography". History Workshop Journal. 71 (71): 98–127. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbq064. ISSN 1363-3554. JSTOR 41306813. S2CID 154796763.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (2014). Vanishing for the Vote : Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the Census. Manchester, U.k.: Manchester University Press.

- ^ a b Tyson, Leonora; Frederick; Lawrence, Emmeline Pethick; Furlong, Gillian (2015), "An early on supporter of women'due south rights", Treasures from UCL (1 ed.), UCL Press, pp. 172–175, ISBN978-1-910634-01-one, JSTOR j.ctt1g69xrh.58

- ^ Whitfield (2001). The Extension of the Franchise, 1832–1931. p. 160. ISBN9780435327170.

- ^ "Offset statue of a woman in Parliament Square unveiled". The Guardian. three April 2017.

- ^ McCann, Kate (6 February 2018). "Suffragettes 'should exist pardoned'". The Daily Telegraph . Retrieved xx August 2020.

- ^ Kent 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Mayall 2000, p. 350.

- ^ "Timeline", Uk 1906 – 1918.

- ^ Purvis 1995, p. 120.

- ^ BBC Radio 4 – Woman'due south Hour – Women's History Timeline: 1910 – 1919

- ^ Peter Rowland (1978). David Lloyd George: a biography. Macmillan. p. 228. ISBN9780026055901.

- ^ Butler, The Electoral System in Britain 1918–1951 (1954), pp. 7–12.

- ^ Butler, The Electoral Organisation in Britain 1918–1951 (1954), pp. 15–38.

Farther reading [edit]

- Arnstein, Walter L. "Votes For Women: Myths and Reality." History Today (Aug 1968), Vol. 18 Outcome 8, pp 531–539; online; covers 1860 to 1918.

- Cairnes, John Elliot (1874). . Manchester: Alexander Ireland & Co.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (1999). The Women's Suffrage Motion: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. London: UCL Press.

- Crossley, Nick; et al. (2012). "Covert social movement networks and the secrecy-efficiency trade off: The case of the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland suffragettes (1906–1914)" (PDF). Social Networks. 34 (four): 634–644. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2012.07.004.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2013). The Women's Suffrage Motion in Britain and Ireland: A Regional Survey. Routledge.

- Fletcher, Ian Christopher, et al eds. Women's Suffrage in the British Empire: Citizenship, Nation and Race (2000),

- Greenwood Harrison, Patricia (2000). Collecting Links: The British and American Adult female Suffrage Movements, 1900–1914. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Griffin, Ben (2012). The Politics of Gender in Victorian Britain: Masculinity, Political Culture and the Struggle for Women's Rights. Cambridge University Press.

- Jenkins, Lyndsey. Lady Constance Lytton: Blueblood, Suffragette, Martyr (Biteback Publishing, 2015).

- Approximate, Tony. Margaret Bondfield: First Woman in the Cabinet (Blastoff House, 2018)

- Kent, Susan Kingsley (2014) [1987]. Sexual practice and Suffrage in Great britain, 1860–1914. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mayall, Laura E. Nym (2000). "Defining Militancy: Radical Protest, the Constitutional Idiom, and Women's Suffrage in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 1908–1909". The Journal of British Studies. 39 (3): 340–371. doi:10.1086/386223. JSTOR 175976. S2CID 145258565.

- Mayhall, Laura E. Nym. The Militant Suffrage Movement: Citizenship and Resistance in Great britain, 1860–1930 (Oxford Upwards, 2003) online

- Pugh, Martin (2012). Land and Society: A Social and Political History of Britain Since 1870 (4th ed.). London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN978-1-780-93041-1.

- Pugh, Martin. The March of the Women: A Revisionist Analysis of the Campaign for Women's Suffrage, 1866-1914 (Oxford Up, 2000) online

- Purvis, June (1995). "The Prison Experiences of the Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain". Women'due south History Review. 4 (one): 103–133. doi:10.1080/09612029500200073.

- Purvis, June; Sandra, Stanley Holton, eds. (2000). Votes For Women. London: Routledge. ; 12 essays by scholars

- Smith, Harold L. (2010). The British Women'south Suffrage Campaign, 1866–1928 (Revised 2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN978-i-408-22823-4.

- Smith, Goldwin (1875). . London: MacMillan and Co.

- Wallace, Ryland (2009). The Women'south Suffrage Motion in Wales, 1866–1928. Cardiff: University of Wales Printing. ISBN978-0-708-32173-vii.

- Whitfield, Bob (2001). The Extension of the Franchise, 1832–1931. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN978-0-435-32717-0.

- Wingerden, Sophia A. van (1999). The Women'due south Suffrage Movement in United kingdom, 1866–1928. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-0-333-66911-2.

Historiography and retentiveness [edit]

- Clark, Anna. "Changing Concepts of Citizenship: Gender, Empire, and Course," Journal of British Studies 42.2 (2003): 263-270.

- DeVries, Jacqueline R. "Pop and smart: Why scholarship on the women's suffrage movement in Britain still matters." History Compass 11.3 (2013): 177-188. online

- DiCenzo, Maria. "Justifying Their Modern Sisters: History Writing and the British Suffrage Movement." Victorian Review 31.1 (2005): 40-61. online

- Gavron, Sarah (2015). "The making of the characteristic film Suffragette". Women's History Review. 24 (six): 985–995. doi:10.1080/09612025.2015.1074007. S2CID 146584171.

- Nelson, Carolyn Christensen, ed. (2004). Literature of the Women's Suffrage Entrada in England. Broadview Printing.

- Purvis, June, and June Hannam. "The women'southward suffrage movement in Britain and Republic of ireland: new perspectives." Women's History Review (Nov 2020) 29#6 pp 911–915

- Purvis, June (2013). "Gendering the Historiography of the Suffragette Motility in Edwardian Britain: some reflections". Women's History Review. 22 (4): 576–590. doi:ten.1080/09612025.2012.751768. S2CID 56213431.

- Seabourne, Gwen (2016). "Deeds, Words and Drama: A Review of the Flick Suffragette". Feminist Legal Studies. 24 (i): 115–119. doi:ten.1007/s10691-015-9307-three.

- Smitley, Megan. "'inebriates', 'heathens', templars and suffragists: Scotland and imperial feminism c. 1870-1914." Women's History Review 11.3 (2002): 455-480. online

Main sources [edit]

- Lewis, J., ed. Before the Vote Was Won: Arguments for and Against Women's Suffrage (1987)

- McPhee, C., and A. Fitzgerald, eds. The Non--Trigger-happy Militant: Selected Writings of Teresa Billington-Greig (1987)

- Marcus, J., ed. Suffrage and the Pankhursts (1987)

External links [edit]

- The struggle for democracy – data on the suffragettes at the British Library learning website

- https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/libraries/athenaeum-and-local-studies/enquiry-guides/womens-suffrage.html Sources for the Written report of Women's Suffrage in Sheffield, UK produced past Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives.

- Gladstone, William Ewart (1892). . London: John Murray.

- William Spud: Suffragettes, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the Showtime World State of war.

- Nicoletta F. Gullace: Citizenship (Great Great britain), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First Earth War.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_suffrage_in_the_United_Kingdom

0 Response to "Review of Following the Money Wealthy Women Feminism and the American Suffrage Movement"

Enregistrer un commentaire